The Homestead Act: A Look at Its Impact and Legacy in America

The Homestead Act of 1862 stands as one of the most transformative laws in American history. Offering 160 acres of free land to settlers willing to farm it, the Act reshaped the country’s landscape, economy, and social fabric. Yet, while it created opportunities for millions, it also brought significant challenges and controversies that continue to shape America’s legacy today.

In this article, we’ll take a closer look at the origins, impact, and lasting consequences of the Homestead Act, from its role in westward expansion to its effects on Native American communities, the environment, and marginalized groups.

Origins of the Homestead Act

The Homestead Act wasn’t born out of thin air—it emerged from a long-standing debate about how America should manage its vast public lands. In the early 19th century, the government sold land to raise revenue, but this approach often excluded poorer citizens from land ownership. By the mid-1800s, Northern politicians championed a new idea: give land for free to those willing to farm it. This policy, they argued, would create a nation of independent farmers while curbing the expansion of slavery into western territories.

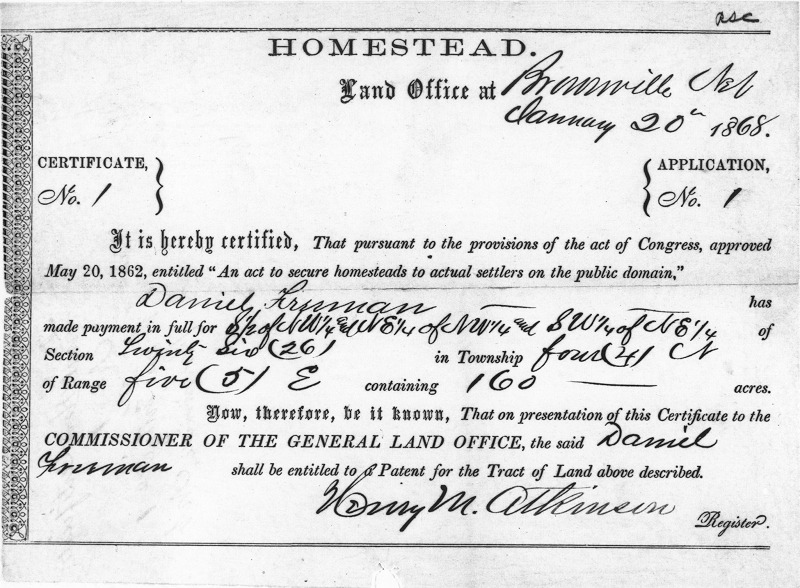

The timing of the Act was no coincidence. Passed during the Civil War and signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on May 20, 1862, it was both a practical tool for economic development and a political strategy. The goal was simple: to populate the West with loyal citizens who would strengthen the Union. The Act promised 160 acres of federal land to anyone—citizen or intended citizen—who could meet the requirements.

Key Provisions and Requirements

If you were living in the 1860s, qualifying for land under the Homestead Act was fairly straightforward. You needed to meet a few criteria:

- Be a U.S. citizen or someone in the process of becoming one.

- Be at least 21 years old or the head of a household.

- Promise to live on the land, farm it, and make improvements over five years.

- Have no history of fighting against the United States.

Once you met these requirements, you could file a claim for up to 160 acres. After living on and improving the land for five years, you would receive full ownership—completely free. Alternatively, if you were in a hurry to own the land outright, you could pay $1.25 per acre after just six months. However, many homesteaders opted for the five-year route, as cash was often scarce.

One of the first individuals to file a claim was Daniel Freeman in Nebraska on January 1, 1863, the very day the Act took effect. Over the following decades, millions of claims were filed, turning vast stretches of federal land into privately owned farms.

Settlement Patterns and Expansion

As settlers flocked to claim land, the American landscape began to change dramatically. Much of the activity centered on the Great Plains, Midwest, and Western territories. States like Kansas, Nebraska, and the Dakotas became hotspots for homesteaders, transforming vast prairies into agricultural hubs.

These settlement patterns didn’t happen randomly. People moved strategically, often following railroads that made travel and transport easier. In the Great Plains, farmers—nicknamed "sodbusters"—focused on crops like wheat, corn, and flax, while settlers in the Southwest and Rocky Mountains planted beans and potatoes.

The Homestead Act wasn’t just about farming—it was about nation-building. By turning territories into productive farmland, the government accelerated the process of admitting new states into the Union. This made homesteading a cornerstone of America’s westward expansion, reshaping not just the land but also the country’s political map.

Challenges Faced by Homesteaders

While the promise of free land sounded enticing, the reality of homesteading was far from glamorous. Settlers faced daunting challenges that tested their endurance and spirit:

- Harsh Weather: From scorching summers to brutal winters, the frontier climate was unforgiving.

- Pests: Insects like locusts could destroy entire crops in days.

- Isolation: Many homesteaders lived miles away from neighbors, leading to loneliness and mental strain.

- Illnesses: Limited access to medical care made even minor illnesses life-threatening.

Meeting the five-year residency requirement was no easy feat. Some settlers abandoned their claims, unable to cope with the physical and emotional toll. Land speculators, railroads, and logging companies often took advantage of these failures, acquiring land that had been intended for farmers.

The challenges weren’t limited to survival. The psychological toll of isolation was immense, especially for women, who often bore the brunt of maintaining households in remote locations. Letters from the time document feelings of despair and longing for community, underscoring the emotional hardships of homesteading life.

Black Americans and Homesteading

For Black Americans, the Homestead Act represented both opportunity and challenge. After the Civil War, newly freed individuals sought to rebuild their lives, and the Act offered a path to land ownership. Communities like Nicodemus, Kansas, became symbols of Black resilience and ambition.

Founded in 1877 by 300 Black settlers from Kentucky, Nicodemus quickly grew into a thriving town with homes, a school, and businesses. Despite its successes, the broader story of Black homesteaders remains underrepresented in historical accounts. Many faced discriminatory practices and violent resistance, particularly in areas where white settlers resented their presence.

Today, descendants of Black homesteaders continue to live on the land their ancestors claimed, preserving an important but often overlooked part of American history.

Environmental Transformation

The Homestead Act’s impact wasn’t limited to people—it also left a lasting mark on the environment. As settlers converted 270 million acres of prairie into farmland, they fundamentally altered ecosystems.

- Native grasses were replaced with wheat and corn.

- Soil erosion and water depletion became widespread.

- Indigenous animal habitats were destroyed.

The environmental consequences weren’t fully understood at the time, but they’re undeniable today. The Dust Bowl of the 1930s, caused in part by poor farming practices encouraged during this period, serves as a stark reminder of the long-term ecological cost of rapid agricultural expansion.

Economic and Social Impact

Economically, the Homestead Act fueled agricultural growth, transforming the U.S. into a global breadbasket. By 1900, one-third of all farms in homesteading states were created through the Act. This rapid development boosted local economies and established farming as a cornerstone of American life.

Socially, the Act contributed to the country’s diversity. Immigrants from Europe flocked to the U.S., drawn by the promise of free land. These settlers brought new traditions, foods, and languages, enriching the cultural fabric of the nation. Women also played critical roles, often working alongside men in farming while managing households and raising families.

An estimated 93 million Americans today are descendants of homesteaders, underscoring the Act’s far-reaching impact on families and communities.

Criticism and Controversies

Despite its successes, the Homestead Act has faced its share of criticism. Key controversies include:

- Native American Displacement: The government granted land that was already home to Indigenous tribes, forcing them onto reservations and disrupting their way of life.

- Fraud and Speculation: Some individuals and corporations exploited loopholes to acquire large tracts of land, undermining the Act’s intent to support small farmers.

- Unequal Opportunities: Women and Black Americans often faced additional barriers to land ownership despite being eligible under the law.

Lasting Legacy in Modern America

The Homestead Act officially ended in 1976, with provisions extending until 1986 in Alaska. Its influence remains visible in the American landscape, as countless farms, towns, and infrastructure owe their existence to this bold experiment in land distribution.

The Act also set the stage for future discussions on land use, conservation, and property rights. While its flaws are undeniable, the Homestead Act remains a powerful symbol of opportunity, perseverance, and the complex journey of nation-building.

By weaving together ambition, resilience, triumph, and sacrifice, the Homestead Act of 1862 left a legacy that continues to resonate today. It’s a story of both progress and cost—one that helps us understand the forces that shaped modern America.