Daniel Freeman: America’s First Homesteader

In the early hours of January 1, 1863, Daniel Freeman did something extraordinary. While others were celebrating the start of a new year, he was at the land office in Brownville, Nebraska, filing the first claim under the Homestead Act of 1862. That moment marked the beginning of a new chapter in American history. But Freeman's story is more than just a footnote—it's about perseverance, imagination, and the drive to build a life from the ground up.

Early Life and Education

Daniel Freeman was born on April 26, 1826, in Preble County, Ohio. He grew up in a farming family that worked hard to make a living. Over time, the family moved to New York and later to Illinois, facing the challenges of starting over in new places. These experiences shaped Freeman's resilience and adaptability.

Life on the farm wasn't easy, and the frequent moves taught young Daniel how to make the best of tough situations. The westward migration trend during his youth exposed him to the opportunities and challenges that came with settling new lands.

Freeman didn't stay on the farm, though. He had bigger ambitions. He studied medicine at Worthington Medical College in Cincinnati, Ohio, and after graduating, he opened a practice in Ottawa, Illinois. For several years, Freeman worked as a doctor, helping people in his community. But with the Civil War looming and the country on the brink of change, so was Freeman's life.

Military Service and Secret Missions

When the Civil War began, Freeman joined the 17th Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment. At first, his medical skills were put to use treating injured soldiers. But his resourcefulness didn't go unnoticed, and soon Freeman was sent on secret missions. He scouted enemy defenses, gathering information critical to Union strategies.

Freeman's work often required him to travel into dangerous territory. As an undercover scout, he not only gathered intelligence but also helped plan strategies that would aid Union forces. These experiences deepened his appreciation for the vast, untamed lands he encountered.

His travels eventually took him to Kansas, where he discovered Nebraska's Cub Creek valley. The fertile land made a lasting impression. It was the kind of place Freeman could see himself settling after the war. The idea of starting fresh on that land stayed with him.

The First Homestead Claim

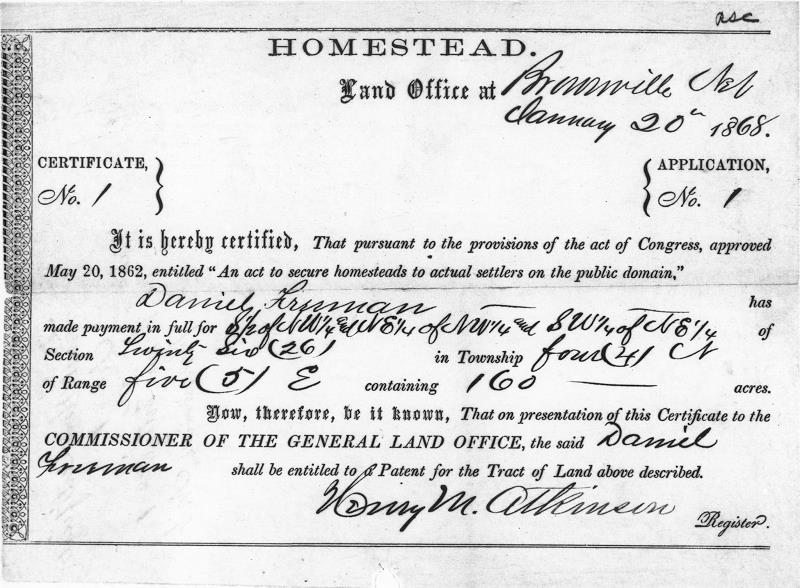

The Homestead Act of 1862 offered 160 acres of public land to anyone willing to farm it for five years. Freeman saw it as the chance of a lifetime. In late 1862, he requested a furlough from his military duties and traveled to Brownville, Nebraska.

The Act had its critics. Wealthy plantation owners and others in positions of power opposed it, fearing it would undermine their control over large tracts of land. Freeman's determination to file his claim was not just about personal gain but also about standing up for a vision of a country where land ownership was within reach for ordinary citizens.

Just after midnight on January 1, 1863, Freeman convinced the land office to open. By filing his claim at that moment, he became the first person to benefit from the Homestead Act. This wasn't just a personal achievement; it symbolized a new era where ordinary Americans could own land and build something lasting.

Building a Life in Nebraska

With his claim secured, Freeman got to work. He built a simple log cabin with two doors and windows to let in light. He plowed and fenced 35 acres, transforming the wild prairie into productive farmland. Over time, he added more buildings, planted crops, and even started an orchard with over 400 peach trees.

The challenges Freeman faced were significant. Prairie fires, harsh winters, and the isolation of frontier life tested his resolve. Yet, he persevered. The land, which initially seemed untamed and intimidating, became a thriving homestead under his care.

Freeman's efforts weren't just about farming; they were about creating a home. His determination to make the land thrive showed what was possible under the Homestead Act. He turned an empty stretch of prairie into a thriving farm.

Community Engagement and Advocacy

Freeman didn't stop at building a farm. He became an active member of his community, serving as County Coroner and Sheriff. Known for being fair and dependable, Freeman earned the trust of his neighbors.

One of his most significant contributions was his fight for secular education. When a local teacher started including religious lessons in public school, Freeman spoke out. He believed that education should be separate from religion, and he took the issue to court. The Nebraska Supreme Court sided with him, setting an important precedent for public education in the state.

Freeman's advocacy for education wasn't just about policy; it reflected his belief in fairness and equal opportunity. He wanted future generations to have access to knowledge without the constraints of religious influence.

Personal Life and Family

Freeman's personal life was just as eventful as his public one. His first marriage, to Elizabeth Wilber, ended in 1861, possibly due to her death or divorce. In 1865, he married Agnes Suiter, a schoolteacher from Iowa. Together, they had eight children, seven of whom survived to adulthood.

Agnes was deeply involved in the family's success. She helped manage the farm and raise their children, ensuring the homestead remained a place of warmth and stability. The Freeman homestead wasn't just a piece of land—it was the center of their lives.

Family life on the homestead wasn't without its challenges. The work was grueling, and everyone had a role to play, from the youngest child to Freeman himself. The farm's success depended on their collective effort.

Expanding the Freeman Homestead

Freeman's ambitions didn't end with his initial claim. Over the years, he expanded his landholdings, building additional structures like a stable, a sheep shed, and a corn crib that was 100 feet long. By the time he completed the five-year requirement to prove his claim, his farm was thriving.

As the farm grew, Freeman also became a mentor to other settlers. He shared his knowledge and experience, helping others navigate the challenges of homesteading. His willingness to support his neighbors strengthened the community around him.

Today, visitors to the Homestead National Monument can see the results of Freeman's hard work. The preserved land and historic buildings give a glimpse into the life of a pioneer who poured everything he had into his dream.

Legacy and National Recognition

Daniel Freeman passed away in 1908, but his impact is still felt. In 1936, Congress officially recognized his homestead as the first claim filed under the Homestead Act. Today, the Homestead National Monument of America honors his legacy. Visitors can explore the land he settled, learn about the Homestead Act, and reflect on what it took to build a life on the frontier.

Freeman's story isn't just about claiming land. It's about what he built with it—a home, a family, and a future. His dedication to his community and his fight for fair education show that he was more than just a farmer. He was someone who wanted to make things better for everyone.

The Homestead National Monument also tells the stories of countless other homesteaders who followed in Freeman's footsteps. Their combined efforts transformed the American landscape, creating thriving communities and shaping the nation's future.

Conclusion

Daniel Freeman's life shows how much one person can accomplish with determination and hard work. From his early days in Ohio to his groundbreaking claim in Nebraska, Freeman's journey is a reminder of the opportunities that come from taking risks and believing in a better future. If you ever find yourself in Nebraska, consider visiting the Homestead National Monument to learn more about his story and the land that changed his life.

Freeman's legacy is more than just history. It's a reflection of the power of vision, the importance of community, and the enduring value of creating something meaningful from the ground up.